January 2

PLETHORIC AIR

A Poem by Luke Kennard

We all laughed at the decomposing clown,

But afterwards guilt sunk upon us

And we got smashed on the balcony.

I had lost my left shoe in the blood.

The doyen and her ten attachés

Scattered blossom on the divans.

We were charmed by a famous puppy,

A dozen gold pins in her forehead;

A tendency to speak ill of the dead.

‘The dead are so stupid,’ she said.

An attaché took me by the temples and ordered,

‘Look: that advertisement on the crevasse;

Notice the inverted commas around “crazy adventures”

Grow bigger than the words themselves,

Framing the very hills and the valleys.

That chap by the fountain changed his name to #:

But ask him why and he’ll say,

“You’ve got to stand out from the crowd, right?”

And other redundant platitudes.

Disappointment kicks you like an ostrich:

Bloody, sandy and hard.

In other news, we grow weary and suspicious –

And we’ll ask you to defend yourself

Using words we already hold to be meaningless.’

I lay back, bumping my head on the war.

Every solid object has been declared part of the war.

I saw the puppy flex her golden needles.

‘You should talk to this guy,’ I said, ‘he’s funny.’

‘Talk to him?’ she spat.

‘I wouldn’t even eat his brain.’

© Luke Kennard, 2005

January 6

THREE MEN IN A BOAT

If you’ve never read “Three Men In A Boat”, so it goes. Originally published in 1888, it was intended to be a more or less serious guide to boating on the Thames (then becoming a serious pastime) with some humorous asides. "Somehow it would not come. It seemed to be all humorous relief,” Jerome said in his memoirs.

Here is a bit of Chapter 6, where the three men in a boat are in the vicinity of Hampton Court.....

Harris asked me if I'd ever been in the maze at Hampton Court. He said he went in once to show somebody else the way. He had studied it up in a map, and it was so simple that it seemed foolish - hardly worth the twopence charged for admission. Harris said he thought that map must have been got up as a practical joke, because it wasn't a bit like the real thing, and only misleading. It was a country cousin that Harris took in.

He said: "We'll just go in here, so that you can say you've been, but it's very simple. It's absurd to call it a maze. You keep on taking the first turning to the right. We'll just walk round for ten minutes, and then go and get some lunch."

They met some people soon after they had got inside, who said they had been there for three-quarters of an hour, and had had about enough of it. Harris told them they could follow him, if they liked; he was just going in, and then should turn round and come out again. They said it was very kind of him, and fell behind, and followed.

They picked up various other people who wanted to get it over, as they went along, until they had absorbed all the persons in the maze. People who had given up all hopes of ever getting either in or out, or of ever seeing their home and friends again, plucked up courage at the sight of Harris and his party, and joined the procession, blessing him. Harris said he should judge there must have been twenty people, following him, in all; and one woman with a baby, who had been there all the morning, insisted on taking his arm, for fear of losing him.

Harris kept on turning to the right, but it seemed a long way, and his cousin said he supposed it was a very big maze.

"Oh, one of the largest in Europe," said Harris.

"Yes, it must be," replied the cousin, "because we've walked a good two miles already."

Harris began to think it rather strange himself, but he held on until, at last, they passed the half of a penny bun on the ground that Harris's cousin swore he had noticed there seven minutes ago. Harris said: "Oh, impossible!" but the woman with the baby said, "Not at all," as she herself had taken it from the child, and thrown it down there, just before she met Harris. She also added that she wished she never had met Harris, and expressed an opinion that he was an impostor. That made Harris mad, and he produced his map, and explained his theory.

"The map may be all right enough," said one of the party, "if you know whereabouts in it we are now."

Harris didn't know, and suggested that the best thing to do would be to go back to the entrance, and begin again. For the beginning again part of it there was not much enthusiasm; but with regard to the advisability of going back to the entrance there was complete unanimity, and so they turned, and trailed after Harris again, in the opposite direction. About ten minutes more passed, and then they found themselves in the centre.

Harris thought at first of pretending that that was what he had been aiming at; but the crowd looked dangerous, and he decided to treat it as an accident. Anyhow, they had got something to start from then. They did know where they were, and the map was once more consulted, and the thing seemed simpler than ever, and off they started for the third time. And three minutes later they were back in the centre again.

After that, they simply couldn't get anywhere else. Whatever way they turned brought them back to the middle. It became so regular at length, that some of the people stopped there, and waited for the others to take a walk round, and come back to them. Harris drew out his map again, after a while, but the sight of it only infuriated the mob, and they told him to go and curl his hair with it. Harris said that he couldn't help feeling that, to a certain extent, he had become unpopular.

They all got crazy at last, and sang out for the keeper, and the man came and climbed up the ladder outside, and shouted out directions to them. But all their heads were, by this time, in such a confused whirl that they were incapable of grasping anything, and so the man told them to stop where they were, and he would come to them. They huddled together, and waited; and he climbed down, and came in.

He was a young keeper, as luck would have it, and new to the business; and when he got in, he couldn't find them, and he wandered about, trying to get to them, and then HE got lost. They caught sight of him, every now and then, rushing about the other side of the hedge, and he would see them, and rush to get to them, and they would wait there for about five minutes, and then he would reappear again in exactly the same spot, and ask them where they had been. They had to wait till one of the old keepers came back from his dinner before they got out.

Harris said he thought it was a very fine maze, so far as he was a judge; and we agreed that we would try to get George to go into it, on our way back.

Link to The Jerome K. Jerome Society website.

January 7

A poem by Mairead Byrne

1

Martha,

It is a long time since we saw you. The cold is terrible. John is engaged. God bless and best wishes for 1002.

Avery

2

Jim,

Do you remember "coby"? We had a laugh. Very best wishes for 957.

Harold

3

Nixie,

Deb said to write you. You know what I want to say. What is your answer? The very best in 1604.

Frank

4

Dervilleen,

When will we see you? Bring butter if you can. God bless and best wishes for 1371.

Kratz

5

Joe,

Tyrone is upset with you about the horse. There's not much to do here. Happy 1749.

Campbell

6

Genna,

If you get this say so. We missed you at Christmas. Take care and best for 1410.

Anka

7

Millie,

Your violin case is being sent with Bertha. Can you collect it? Happy New Year from all at 41 and best wishes for 2032.

Terence

8

Francis,

I think you should listen to Molly. What's it like there? With every good wish for 1916.

Sarah

9

John,

Do you like these "boots"? I thought they'd suit fine. Thinking of you and wishing you all the best in 1799.

Grant

© Mairead Byrne, 2004

January 9

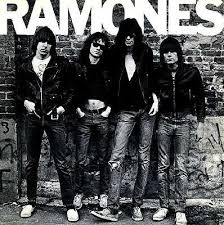

GABBA GABBA HEY ETC.

Friday evening Jez and I went to see The Ramones movie – “End of the Century” . What a great film! I hate the word “rockumentary” but that’s what it was, and it was cracking. It’s full of honesty, emotion, love and hate, brilliant archive material of obscure performances, and fantastic music. Sometimes it’s sad and sometimes it’s funny. It scores too because everyone involved has their say, so all the arguments and conflicts come out kind of even. There were lots of good moments, but my favourite has to be when Joey’s brother is talking about how one night after a gig at CBGB’s, he was coming out of the club with Joey and a photographer asks him to step aside so he can take a picture of Joey on his own. It was the moment, he says, when Joey began to change and grow in confidence. From that moment on he started to get girls -- or rather, “girls who weren’t on medication.”

Friday evening Jez and I went to see The Ramones movie – “End of the Century” . What a great film! I hate the word “rockumentary” but that’s what it was, and it was cracking. It’s full of honesty, emotion, love and hate, brilliant archive material of obscure performances, and fantastic music. Sometimes it’s sad and sometimes it’s funny. It scores too because everyone involved has their say, so all the arguments and conflicts come out kind of even. There were lots of good moments, but my favourite has to be when Joey’s brother is talking about how one night after a gig at CBGB’s, he was coming out of the club with Joey and a photographer asks him to step aside so he can take a picture of Joey on his own. It was the moment, he says, when Joey began to change and grow in confidence. From that moment on he started to get girls -- or rather, “girls who weren’t on medication.” 2. Litter

Alan Baker at Leafe Press has just posted the first showing of a new on-line magazine, Litter. Click here, as they say. It’s damn fine. Poets include Clive Allen and Kelvin Corcoran, and there is visual work from Rupert Loydell and Alan Halsey. There’s not a dud anywhere in this first batch of, well ..... litter.

3. Kenneth Rexroth

And while I’m at it, I’ll mention how I just spent the last three or four weeks in the company of a book the size of a house brick: The Complete Poems of Kenneth Rexroth. My review of it has arrived today at Stride, and since I like the book a lot the review is something of a collector’s item ….. Well, that’s not true, actually. I’ve written lots of very positive reviews about lots of very good books of poems. People, including me, only seem to remember the particularly devastating and critical ones. Anyway, I liked this house brick loads, and you can go straight to the review by clicking on this little maroon Rexroth.

4. Funeral

Finally, my pal Mr Belbin has been blogging somewhat busily of late, and it’s worth catching up on. He has also just popped in for a cup of tea, and I’ve burned a copy of a record he brought around by a Canadian band called The Arcade Fire. No, I've never heard of them either. The record is called “Funeral” (the title itself makes it a record I had to have) and behind the chat it sounded really good, so I’m going to go and play it again now. He also lent me the brand spanking new Aimee Mann Live DVD; he’s a capital fellow. So, that’s my Sunday evening sorted. The Arcade Fire and Aimee Mann. I probably should read a poem or two, but I don’t think I’ll have the time.

January 11

Review by Terry Kelly

Mischief Night – New & Selected Poems by Roddy Lumsden (Bloodaxe, £8.95)

If you want mainstream poetic hip, Roddy Lumsden’s your man. A witty poet, combining technical resourcefulness with a keen eye for the sort of transient cultural detritus my late Mam called “all the go,” Lumsden never seems to strike a wrong note in the halls of hipness. The Bloodaxe blurb to Lumsden’s first book, “Yeah Yeah Yeah” (1997) trumpeted the poet’s previous life as a quiz machine expert and even quizmaster, and his poems are often packed with cultural trivia of all varieties. When Lumsden’s collection “The Book of Love” was selected as the Poetry Book Society Choice for summer 2000, he admitted in a PBS Bulletin to flavouring his work with what he called “strange details and odd facts.” Lumsden goes on to provide examples of these nuggets of literary, personal and cultural arcana. One more than tongue-in-cheek commentary to the poem ‘Love’s Young Dream’ reads: “I deny suggestions that Simon Armitage has been a major influence on my work. However, I fully admit that my knowledge that 615s are trendy jeans was culled from Simon’s packing list for Iceland in Moon Country.” This is wheels-within-wheels literary chat, since the prospective Lumsden reader would need to know that Armitage collaborated with fellow poet Glyn Maxwell on a 1996 book retracing the steps of Auden and MacNeice’s earlier poetic joint effort, ‘Letters from Iceland’, in the 1930s. The PBS notes range from references to ‘mother-blame’ in feminist writings, to a condensed future novel for Alan Warner after he favourably reviewed a Lumdsen collection, to the revelation that a Guardian hack once published a piece of literary gospel spouted by the poet. A poem in “Mischief Night” called ‘My Superstition’ (drawn from his last collection, 2001’s “Roddy Lumsden Is Dead”) takes literary name-dropping to extremes, as the poet watches an insect navigate his bookshelf:

When Lumsden’s collection “The Book of Love” was selected as the Poetry Book Society Choice for summer 2000, he admitted in a PBS Bulletin to flavouring his work with what he called “strange details and odd facts.” Lumsden goes on to provide examples of these nuggets of literary, personal and cultural arcana. One more than tongue-in-cheek commentary to the poem ‘Love’s Young Dream’ reads: “I deny suggestions that Simon Armitage has been a major influence on my work. However, I fully admit that my knowledge that 615s are trendy jeans was culled from Simon’s packing list for Iceland in Moon Country.” This is wheels-within-wheels literary chat, since the prospective Lumsden reader would need to know that Armitage collaborated with fellow poet Glyn Maxwell on a 1996 book retracing the steps of Auden and MacNeice’s earlier poetic joint effort, ‘Letters from Iceland’, in the 1930s. The PBS notes range from references to ‘mother-blame’ in feminist writings, to a condensed future novel for Alan Warner after he favourably reviewed a Lumdsen collection, to the revelation that a Guardian hack once published a piece of literary gospel spouted by the poet. A poem in “Mischief Night” called ‘My Superstition’ (drawn from his last collection, 2001’s “Roddy Lumsden Is Dead”) takes literary name-dropping to extremes, as the poet watches an insect navigate his bookshelf:

The bug parades past Burnside, Copus,

bypasses Brewer’s, Chambers, Nil Nil…

Most fairly literate readers would spot the references to the famous dictionaries, but how many would pick up on the allusions to contemporary poets John Burnside, Julia Copus and Don Paterson’s Faber debut, “Nil Nil”? Clearly, Lumsden takes no prisoners when it comes to his readers. A fairly comprehensive knowledge of contemporary verse is pretty essential. There’s also a fictive, self-aware quality in even the most autobiographical of Lumsden’s poems, as though he has one eye on his literary audience or even prospective critics. There’s a form of extreme poetic solipsism at work in much of Lumsden’s work. The poet even uses a quotation from a TLS review of one of his previous books as an epigraph to the ironically titled ‘My Pain’:

It’s like what I told the lassie from the local paper:

I do not suffer for my art, I just suffer.

Not afraid of dismantling ironic distance to place himself centre-stage in his own poetic melodrama, this literary strategy reaches its pinnacle in the title sequence, ‘Roddy Lumsden Is Dead’, which is partly an exploration of previous mental illness. His Author’s Note to the earlier collection about this bipolar condition could also be an apt definition for Lumsden’s energetic poetic egotism: “It is sometimes described as ‘filmic,’ ie the sufferer feels himself to be a character in the film of his own life.” Or try this, from ‘My Reflection’:

Late-night and bearded, framed in a mirror

as make-believe Rouault judge, white-faced and counting

his sins and his blessings – although I have neither –

I call myself sufferer, suitor, survivor…

With Lumsden’s authoritative grasp of high, low and various strands of popular culture, the reader is as likely to find references to just-breaking indie bands as Douglas Dunn’s recent ‘break-up book’ “The Year’s Afternoon”. One poem even namechecks the wonderful Denise Riley in its epigraph, proving this Scottish poet has looked beyond the Faberised literary horizon to the outskirts of the Cambridge School. It’s clear Lumsden knows his stuff and possesses the kind of poetic brio most young writers can only dream about. The title poem from his latest collection, “The Drowning Man”, is an example of Lumsden’s ability to make dizzying imaginative connections:

In the elsewhere, I see majorettes, the ends

of rummage sales, the heaving panther

coiling round an oak, I think I see

a dim light from a forest shack, I think I see

the outline of an arm through tinted glass,

my children sliding down the sky, not born.

This welds an Audenesque imaginative reach with a rangy, New York School freedom. Occasionally, the literary knowingness, particularly in the earlier work, can become rather wearing, like Simon Armitage on speed. (In fact, I have a clipping of a review of Lumsden’s first book by the late William Scammell, who suggested the young poet could become a member of an imaginary poetic movement called the “School of Simon Armitage”). But Lumsden strikes me as much sharper than the Bard of Huddersfield. Plus, he can reveal a heart behind the sharp cadences and his shield of hip references:

So many, so many songs

for the suicides, for the lives

docked in middle age;

those taken in the evening hiss…

(from ‘The Tremendous Few’)

Lumsden explored his battle with mental illness in the bravely titled “Roddy Lumsden Is Dead” (Wrecking Ball Press, 2001), which unfortunately sank without trace because of distribution problems (a similar fate beset Brendan Cleary’s last collection with the same press). But it’s Lumsden’s cultural accuracy that repeatedly strikes home:

Wrapped in the The Scotsman,

the family hamster

in a Saxone shoe box

four feet under.

(from 'My Funeral')

That shoe box just had to be from Saxone for the line to work. Lumsden takes his foot off the post-modern accelerator pedal in some of the more emotionally open latest work in this big Bloodaxe selected, proving he can encompass a wide emotional as well as literary-cultural landscape in his glittering poems.

© Terry Kelly, 2005

January 16

I’ve just been to Brighton for a few days. Both my sons live there with their girlfriends, and each time I go there I fall in love with it all over again. I’m sure it has its rubbish side like every other place, but I enjoy the cosmopolitan feel, its architecture (I mean the good, old Regency-type stuff - not the godawful 1960s concrete blocks of offices and flats), and most of all – the Sea.

I love the sea, but I could never be a sailor. I like being beside it (not, I must add, in bathing costume) and within earshot of its incessant noise. For twenty years or so I lived on the Suffolk coast, in Felixstowe, not quite within earshot of the North Sea but only a few minutes walk away from it. I used to love walking on the beach on November evenings, when the wind whipped in from the East like a load of ice cold knives aimed at your head. For five years I worked for a shipping agent in the Docks. I used to go on board cargo vessels and make sure the Captain and crew had all the stores they needed, and sort out the cargo manifest and what have you; I was kind of the link between them and dry land. Okay, they had a gangway, too, but I was more human. It was a pretty interesting job. I learned how to have whiskey for breakfast at 6 o’clock in the morning and how to go back to the office at half past eight and appear not to be drunk. One day a sailor fell down the narrow gap between the side of our ship and the dock and was killed. Every now and then one of the Captains would say that maybe one day I could go on a round trip with them, but it never materialised. I wasn’t too bothered. Sweden and the North Sea in midwinter didn’t seem a great proposition. And they weren’t very big ships, and it didn’t look particularly comfortable down below in the living quarters. Cosy, yes; comfortable, no. Every now and then we’d get one of the big transatlantic container ships in, but I was never offered a round trip to Miami. Felixstowe was (and probably still is) the biggest container port in the country. One day a docker was hit by one of those huge mobile container carriers that move containers around the quayside. It sliced him in two at the waistline. I missed seeing it by about a minute. The bloke I worked with, an old chap who’d been a seaman all his life and had been through more shit than most, saw it happen. I’ve never seen anyone whiter or more shaken up either before, or since. He needed more than one shot of Scotch to face the rest of the day. When I went back to the ship later that morning they were hosing the quayside down, cleaning up the mess. The only time I actually went to sea while I worked that job was for a learning trip my employers sent me on to see the docks in Ostend and Dunkirk. They were very dull – see one docks, you’ve seen them all, to be honest - but the coachload of other dock-type people I went with included a bloke called Harry Gibb, who was a boxing referee. He refereed international bouts, including a fight between Henry Cooper and Joe Bugner. It was big-time televised stuff, and he did it in his spare time from working in a London dockyard. Boy, he had some stories. We laughed a lot, and got drunk again, and looked in red light windows in Ostend. I was only a lad, with a wife and two kids. But I’m digressing. Back home, sometimes we’d have to work all night, and you’d see the darkness fall on the sea, and the day dawn. But I could never be a sailor; I’m too much of a wimp.

I love the sea, but I could never be a sailor. I like being beside it (not, I must add, in bathing costume) and within earshot of its incessant noise. For twenty years or so I lived on the Suffolk coast, in Felixstowe, not quite within earshot of the North Sea but only a few minutes walk away from it. I used to love walking on the beach on November evenings, when the wind whipped in from the East like a load of ice cold knives aimed at your head. For five years I worked for a shipping agent in the Docks. I used to go on board cargo vessels and make sure the Captain and crew had all the stores they needed, and sort out the cargo manifest and what have you; I was kind of the link between them and dry land. Okay, they had a gangway, too, but I was more human. It was a pretty interesting job. I learned how to have whiskey for breakfast at 6 o’clock in the morning and how to go back to the office at half past eight and appear not to be drunk. One day a sailor fell down the narrow gap between the side of our ship and the dock and was killed. Every now and then one of the Captains would say that maybe one day I could go on a round trip with them, but it never materialised. I wasn’t too bothered. Sweden and the North Sea in midwinter didn’t seem a great proposition. And they weren’t very big ships, and it didn’t look particularly comfortable down below in the living quarters. Cosy, yes; comfortable, no. Every now and then we’d get one of the big transatlantic container ships in, but I was never offered a round trip to Miami. Felixstowe was (and probably still is) the biggest container port in the country. One day a docker was hit by one of those huge mobile container carriers that move containers around the quayside. It sliced him in two at the waistline. I missed seeing it by about a minute. The bloke I worked with, an old chap who’d been a seaman all his life and had been through more shit than most, saw it happen. I’ve never seen anyone whiter or more shaken up either before, or since. He needed more than one shot of Scotch to face the rest of the day. When I went back to the ship later that morning they were hosing the quayside down, cleaning up the mess. The only time I actually went to sea while I worked that job was for a learning trip my employers sent me on to see the docks in Ostend and Dunkirk. They were very dull – see one docks, you’ve seen them all, to be honest - but the coachload of other dock-type people I went with included a bloke called Harry Gibb, who was a boxing referee. He refereed international bouts, including a fight between Henry Cooper and Joe Bugner. It was big-time televised stuff, and he did it in his spare time from working in a London dockyard. Boy, he had some stories. We laughed a lot, and got drunk again, and looked in red light windows in Ostend. I was only a lad, with a wife and two kids. But I’m digressing. Back home, sometimes we’d have to work all night, and you’d see the darkness fall on the sea, and the day dawn. But I could never be a sailor; I’m too much of a wimp.

I just re-read a couple of Joseph Conrad things. This is more or less a coincidence. I once wrote a poem called “For Joseph Conrad”, which was partly because I like his work a lot, and partly as an excuse to write a poem that involved a trip around the world and mention of lots of places I’d never been to on boats that didn’t exist. I also tried to be witty and amusing, because I was beginning to work out that poems didn’t have to be about the cosmos and why, but I’m not sure how successful I was. This is a bit of it:

In San Francisco it was foggy,

as usual, though that didn’t alter

how we ate our way across the city.

A few days later, finding ourselves

wandering aimlessly outside a condo

complex at Oakland we took up with

a couple of guys who were headed

for Vietnam. This was quirky enough

to be too good to miss, so we hopped

aboard Darkness and Light and

trusted someone knew the route.

Someone did know the route, but

nobody knew how to steer the boat;

in New Zealand we cut our losses

and bought berths on The Cutlass,

though the mate’s eye patch, and hook

where his hand should’ve been, gave

me nightmares.

Of course, a lot of Conrad is about the cosmos. I always loved those big grandstand (and often incomprehensible) paragraphs where he goes on and on about the vast silent immensity of great unfathomable enormousness. And this kind of thing:

Yet at midnight he turned out to duty as if nothing had been the matter, and answered to his name with a mournful 'Here!' He brooded alone more than ever, in an impenetrable silence and with a saddened face. For many years he had heard himself called 'Old Singleton,' and had serenely accepted the qualification, taking it as a tribute of respect due to a man who through half a century had measured his strength against the favours and the rages of the sea. He had never given a thought to his mortal self. He lived unscathed, as though he had been indestructible, surrendering to all the temptations, weathering many gales. He had panted in sunshine, shivered in the cold; suffered hunger, thirst, debauch; passed through many trials -- known all the furies. Old! It seemed to him he was broken at last. And like a man bound treacherously while he sleeps, he woke up fettered by the long chain of disregarded years. He had to take up at once the burden of all his existence, and found it almost too heavy for his strength. Old! He moved his arms, shook his head, felt his limbs. Getting old.... and then? He looked upon the immortal sea with the awakened and groping perception of its heartless might; he saw it unchanged, black and foaming under the eternal scrutiny of the stars; he heard its impatient voice calling for him out of a pitiless vastness full of unrest, of turmoil, and of terror. He looked afar upon it, and he saw an immensity tormented and blind, moaning and furious, that claimed all the days of his tenacious life, and, when life was over, would claim the worn-out body of its slave.

I don’t think my squib of a poem was trying to capture quite the same thing, to be honest. Which is good, because it didn’t capture it at all. But yes, I’d like to live by the sea again. I’d quite like to live in Brighton, because my kids are there, and you can get very good lunches at The Hop Poles on Middle Street, I think it is. But I can’t afford the rents or the house prices. I’d have to get a full-time job.

January 18

LAUGH OR CRY. POSSIBLY BOTH

Today comes this news: “Hungarian-born George Szirtes' collection of poetry has picked up the £10,000 T.S. Eliot Prize. His book, “Reel”, was judged the best collection of new poetry published in the UK and Ireland. He was handed his prize money by T.S. Eliot's widow Valerie at an award ceremony in London. His work was described as "a brilliantly virtuosic collection of deeply felt poems concerned with the personal impact of the dislocations". Chair of the judges, Douglas Dunn, said: "The judges were impressed by the unusual degree of formal pressure exerted by Szirtes on his themes of memory and the impossibility of forgetting." (This news quote comes off the BBC website.)

Today comes this news: “Hungarian-born George Szirtes' collection of poetry has picked up the £10,000 T.S. Eliot Prize. His book, “Reel”, was judged the best collection of new poetry published in the UK and Ireland. He was handed his prize money by T.S. Eliot's widow Valerie at an award ceremony in London. His work was described as "a brilliantly virtuosic collection of deeply felt poems concerned with the personal impact of the dislocations". Chair of the judges, Douglas Dunn, said: "The judges were impressed by the unusual degree of formal pressure exerted by Szirtes on his themes of memory and the impossibility of forgetting." (This news quote comes off the BBC website.) If this all doesn’t say something about something I don’t know what does. Laugh or cry.

The picture, by the way, is neither of T.S. Eliot nor George Szirtes. It is a mouse. Incidentally, Rupert has a new website, which is well worth a visit.

January 19th, 2005

Lee Harwood was absolutely excellent, reading at The Flying Goose in Nottingham on Tuesday evening. As Clive Allen and I walked across to the pub afterwards, we agreed that Harwood had read really well. He has a gentle, almost diffident manner, and he’s pretty softly spoken, but there was also a quiet but strong confidence about his delivery which was very impressive. Also, and this is good too, he wasn’t solemn or precious about anything – in fact, when a latecomer came in moments after Harwood had begun his reading, and apologised for interrupting, Lee just said, “It doesn’t matter – it’s only poetry.” Then he picked up where he’d left off, reading with a hint of a smile.

Lee Harwood was absolutely excellent, reading at The Flying Goose in Nottingham on Tuesday evening. As Clive Allen and I walked across to the pub afterwards, we agreed that Harwood had read really well. He has a gentle, almost diffident manner, and he’s pretty softly spoken, but there was also a quiet but strong confidence about his delivery which was very impressive. Also, and this is good too, he wasn’t solemn or precious about anything – in fact, when a latecomer came in moments after Harwood had begun his reading, and apologised for interrupting, Lee just said, “It doesn’t matter – it’s only poetry.” Then he picked up where he’d left off, reading with a hint of a smile.

Last year sometime I wrote a review (which was published in Staple magazine) of Harwood’s Leafe Press pamphlet “Evening Star”. I’m reprinting it here, and there is a point in doing this, which I’ll come to afterwards…..

*

“Evening Star” is Lee Harwood’s first collection of new poems for some time, which in itself makes it well worth having a look at. The first poem, “Salt Water”, reminds us how good Harwood can be:

The complexity of a coral reef

the creatures sunlight

shafting down through the crystal sea

water the flicker of shadows

light wavering and fading

into the depths

This is how the poem begins. There’s nothing difficult about reading this writing. What is difficult is the poet’s achievement: with deceptive simplicity Harwood has the ability to suspend the object or the moment and allow us a clear examination of what he wants us to see. The line-breaks, the hiatuses, the control the poet exercises over the pace at which we read this -- believe me, that’s difficult.

The poem is two pages long, and only when it’s done do we find it dedicated to “Joey Peirce/Harwood, who lived 11-14 March 1997”. And it’s then we are turned back to the poem and its significances, such as:

“Polyps” the books say coral

a tube with a mouth at the end

surrounded by tendrils to catch

small creatures

A world of soft tissue

That the dedication comes after the poem, and not immediately after the title, is indicative of the poet’s characteristic restraint. I like it that, although the poems largely possess a fidelity to the thing and don’t mess around --

the mudflats and saltings shine

as the children run by

along marsh edge and the high dyke bank

egret and oystercatcher dunlin and sandpiper

(from “Pagham Harbour Spring”)

-- they also are sometimes not quite as easy to “get” as they might be. “Fragment Of An Indecipherable Inscription” seems a straightforward enough account of a family outing until the third stanza introduces an unexpected dissonance:

In the distant town can we buy food?

Like refugees. Like distant bombs.

A stumbling return. Will you still be there?

There are times I really like not knowing what’s going on. I don’t necessarily read poems “to understand”. But there are other times I feel frustrated. “The Wind Rises: Istvan Martha Meets Sandy Berrigan” manages this trick: naming a modern Hungarian composer (“The Wind Rises” is one of her works, by the way. Thank you, Google) and the wife of American poet Ted Berrigan in one title is fine: there are no rules about this stuff. But I’m struggling to relate them to the poem. I suspect Harwood knows something (probably a lot of things ) I don’t. I’m not sure I appreciate being made so blatantly aware, though. But the poem is okay, and whilst I’m not quite sure where it’s coming from I like where it goes, and I‘m enjoying re-reading it.

Harwood is something of a mixed bag these days. He can still be what would once upon a time have been called quite radical (although now it doesn’t raise an eyebrow) by slipping in to one poem a hefty wedge of prose quotation from Charles Darwin’s journals, and there are plenty of instances where the rather clunky prosaic quality of the lines might be read as another example of the modern poet saying Hey, look at me, I’m a poet being determinedly non-poetic. And he can be more than a bit minimal, too: a little poem like “Eric Satie” doesn’t really want to give up much of itself to you. Which makes it rather interesting.

But his real strength is on display in a poem like “Cwm Nantcol”:

Light slanting down on this high green valley.

Wind blowing, bending the reeds, hawthorn trees,

the scattered clumps of rowans.

Massive slabs of rock,

like ribs down the sides of the cwm,

clawed and scoured, ground and polished

by the glaciers of “Ancient Times”.

And now silver birch, oaks, tender mosses

grow in the shadows of these purple grey bluffs.

Such an emptiness. Here where sheep die

trapped in a fence or drowned in the river,

where a single track winds up into the mountains,

ends at the last farm, a stream, cattle

up to their shanks in a bog……

But interestingly, to my ear, this poem also has a weakness that crops up several times throughout the collection. It’s what you might call ‘the poet thinking out loud’:

But why this fascination? the many returns

to this place? A comfort?

The rhetorical questions weaken the poem considerably. One is tempted to refer to the old workshop cliché about not telling too much, just let it show. And Harwood does this kind of thing quite a lot:

Is that what getting old is?

Learning to live like this - that strength

increasingly needed. Or sink into gaga?

(“The Wind Rises”)

Talking to you? to myself? to the “ether”?

(“5 Rungs Up Sassongher”)

If the myths were put aside, and we…?

Would the mirrors be clear and glitter? a rainbow

flickering on their bevelled edges? I doubt it.

(“Hampton Court Shelter”)

But this is to concentrate on the negative. There’s a lot to like in these poems. The third section of “5 Rungs Up Sassongher” -- “The Joyous Lake” -- is quite beautiful:

A sort of simplicity, not babble, to hold to

firmly but gently. Intense and. Beautiful as

a spray of moth orchids on the sunlit table.

And a lasting memory I’ve taken from reading these poems are a couple of lines from the second poem in the book:

the children running on the dyke bank

absorbed in this world

echoed (I’m sure not unwittingly) in the fifth section of “Five Pieces for Five Photos”:

We smile at the children

absorbed and opening their world

Which is really cool. Yes, there’s good stuff here. My initial impression had been that it was all rather dry, but the poems repay continued attention and re-reading. Definitely recommended……

*

I've changed my mind about some of what I've said in there, but no matter. My main reason for reprinting this is that Harwood read a poem I mention, “The Wind Rises: Istvan Martha Meets Sandy Berrigan”, at the end of his first set. In the interval, he and I had a really nice chat, taking in subjects ranging from the fact that it turns out he lives almost within shouting distance of one of my kids in Brighton, to how good New York is for charging the batteries, and a couple of other things in between. But, more to the point, I drew his attention to how I’d mentioned that particular poem in my review (which Lee had seen), and how hearing it read was really interesting. I think I meant that I’d got more out of it, hearing the poet’s voice. Lee had mentioned in his introduction to the poem something about Istvan Martha’s music, and how Sandy Berrigan is a quilt maker. But there was also the matter of hearing the poet, the rhythms of his speech, and his breaths. Lee also told me how he’d been trying to get something of the music into the poem. I know this is kind of neither here nor there stuff in some respects, because you have a book and you have the poem on the page and most of the time that’s it, and it has to be enough. But if you can get more, go for it. Lee and I agreed for example that, however much we might have admired John Ashbery’s poetry before we ever heard him read, once you have Ashbery’s somewhat monotone delivery laced with his sense of mischief and pleasure to go along with it you have an added dimension that can only be good. Harwood’s reading was another excellent example of this – something has been added to my future reading of the poems, and I’ll own up to how some pieces which had not made a deal of an impression on me at the time of writing that review, on hearing them read aloud by the bloke who wrote them, they sounded really good, and I’m going back to them immediately.

This is not by any means to imply a failure in the writing, nor necessarily a failure in my reading, although the latter is more than likely. Reading "The Wind Rises...." now, very slowly, pausing slightly where the text tells me to pause, and still hearing the poet’s voice, I’ve learned something and I’m richer for it. I said in the review how the poet controls the pace at which we read. I now realise that at times when I was reading the poems I was wholeheartedly and rather dumbly ignoring all that and going at some of it like a train. It helps if the reader does his share of thinking, I guess. If I have a point to make it’s that poetry readings are, in principle, good things. The problem, of course, is that more often than not poetry readings are pretty dreadful things. But when you hear someone who is an absolute master of the craft at work, and when they are at the top of their game, it’s an exhilarating experience. Lee Harwood at The Flying Goose was exactly that.

January 23

1.

New issues of two magazines have recently plopped on to the doormat: Tears in the Fence has a cover this time which hasn’t worked: it appears to be of a dark green dog stood in a dark green field at night, all printed on dark green card. Even seen with a flashlight it’s quite a lot of dark green. But that’s only the cover. Inside it’s the Fence’s usual intelligent mixture, although I have to say I’ve read very little of it as yet. No time. Writers include Peter Dent, Robert Sheppard, Norman Jope and K.M. Dersley. Anyway, it’s £6.00 from 38 Hod View, Stourpaine, Blandford Forum, Dorset, DT11 8TN, and should be one of the magazines you don’t ignore.

I’ve read none at all of the new Ambit, #179, which arrived Friday. This is £6.50 from 17 Priory Gardens, London N6 5QY. Ambit must be one of the most long-lived poetry magazines in the UK. People in this one include …. oh, it’s me! Wow.

2.

When I was in Brighton recently I bought a few secondhand books. I said I wouldn’t but I did. One was a novel by Ronald Firbank, called “Prancing Nigger”. Yes, it’s an unfortunate title. Apparently it was also published as “Sorrow in Sunlight”. I bought it because I had a vague recollection I’d come across Firbank’s name somewhere, and I think it was by way of John Ashbery, or James Schuyler, or someone from that area. Of course, I could be completely wrong. But somewhere in the recesses of my head I had him down as a stylist, and someone to at least have a look at. Otherwise, I knew nothing of him, and had certainly never come across any of his books.

“Prancing Nigger” dates from 1925. Firbank seems to hover around as some kind of link between the writing of the 1890s, about which I don’t know much but which I understand to be rather effete and dandyish, and the modernists of the 1920s, about which I know rather more. It’s an intriguing little book. I called it a novel, but it’s only 70 pages long, so perhaps ‘novella’ would be more accurate. It has great elegance, and is primarily dialogue. That’s why I’m pretty sure of the Ashbery/Schuyler thing – Ashbery was an admirer of Henry Green, another master of the dialogue novel, and there’s also the Ashbery/Schuyler collaborative novel “A Nest of Ninnies” in a similar mould. There’s also a good deal of ellipsis of sorts (if that’s the correct term), which again is somewhat characteristic of all these writers. For example, there’s an earthquake happens, and you have to be paying proper attention to realise it. When you go back and re-read the less than a page in which it occurs, it’s so deftly done one can only admire. However, one of my favourite passages is about some flowers:

But in their malignant splendour the orchids were the thing. Mrs. Abanathy, Ronald Firbank (a dingy lilac blossom of rarity untold), Prince Palairet, a heavy blue-spotted flower, and rosy Olive Moonlight, were those that claimed the greatest respect from a few discerning connoisseurs.

I’ve since discovered a few things about Ronald Firbank. He had sunstroke as a child which left him a little frail. He spent a lot of time alone. He inherited money that allowed him to travel a lot. He wore a lounge suit, a bowler hat, and carried a cane and gloves. He painted his fingernails. It’s also alleged that he was afraid of eating, and drank only champagne, complemented by some flower petals and a single grape. I don’t know if this is true. I hope it is.

3.

Jez and I have been to another movie. It was Team America: World Police. I am wondering how I can claim back my admission money. I thought it was going to be funny and politically cutting edge. It had one good joke in it, which was then ruined by going back over it again and again. As for politics, the film spent all its energy taking swipes at actors. Why? Who cares about actors? But don’t take my word that it’s rubbish. Go see it and find out for yourself.

January 26

A PICTURE

I have spent the last few days

working on this picture

for you. In it there is a tree,

a yellow chair (the sort

with a straight back and a cane

seat), a sky the colour of lilacs

and, on the chair, a bundle

of grey twigs. I hope

you like it. I hope you can see

your hand in it. The tree is

probably some sort of chestnut,

but I wouldn’t know a chestnut

from a beech and I wouldn’t know

a beech if it walked up to me

and introduced itself. I don’t know

what it means and this is why

I’ve been working on it: so that

I can send it to you and you can

tell me. Do you think the chair

is you or are you the tree?

Are the twigs and the chair symbols

of resurrection? Is the sky

in any way important?

Is the fact that it is clearly winter

at all relevant? It’s not difficult

to see why I needed to get some help

in figuring out what I’ve done.

I’m sure you will

come through on this for me

and tell me what’s behind it,

and if there’s anything to praise

in it. After all these years

surely we can speak honestly,

in words we can both understand.

January 28

I'VE LOST THE PLOT

January 30

Review by Rupert Mallin

Translating Into Love Life’s End by Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke

The Weight of Cows by Mandy Coe

The New Girls by Sue Dymoke

Laughter From The Hive by Kate Foley

(all from Shoestring Press, £7.95p each)

I was stood in the drizzle talking to young Ben, a delegate like myself to Norwich”s “New Writing Types Conference.” Ben and I agreed that a lot of English poetry is anecdotal, even whimsical, shy of abstract subjects and language. However, my new acquaintance was of the certain opinion that good poetry (his term) rises to the surface in much the same way as wheat and chaff are separated by sifting. Of course, many of us do not possess the correct sieve and we are not paid to sift.

I wish Ben luck in ending up as golden wheat. According to the Conference, it is not a matter of luck, education or who you know but a path (the holy grail to the sieve?) of progression - in form, voice and subject. Of course, every subject is available but “observation” is key to this progression - observation of a moment (breakfast), ones environment (clothes lines, bees, etc) and ones emotions (love, death, etc). Yet, perhaps notions of observation enshrine reservation?

Not only on “Exultations & Difficulties” has poetry-death reared its ugly head. Peter Porter and Douglas Dunn were recently in conversation on the radio relating how the early deaths of family members had moved them (obviously). To cope with their grief and terrible loss they wrote poems to their lost loved ones. Early deaths have touched my life too. Very many of us. I am stating the obvious: poetry isn’t death, it is life and the lament doesn’t just concern human loss but a perceived certainty that has been broken by death. We live in uncertain, breaking and deathly times.

There are two directions one can take in writing of - or out of - the present times: gather up the toolbox of craft, close the door, create an oasis of certainties and get sieving; or abstract outwards from this breakage yard of our age.

“Translating Into Love Life’s End” is an uplifting volume of poetry as Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke takes on death, lifts it like a dress and lives with it as if love. She takes “murderous sadness” and literally makes a meal of it:

The murderous sadness

when everything I loved that is still alive

and does not concern me anymore

I put through the mincer of time

and lightly sprinkle with concentrated sorrow

the evening meal called “life”

which is still being served

(from “A Recipe For Life”)

Her relationship with death also encompasses her work as a translator and poet crossing geographical and mythical borders. She is in conversation with her poetry and her soul and a male “other” yet her rivers and veins are universal and pulse with life. She makes poetry physical, as in “Translating Into Love Life”s End.” While she cannot physically touch that which has gone, like the dead, like a departed lover, she can imagine. Yet, her departed is also the text itself:

I want to know how you strip

how you open up

so I look for your habits

in between your lines

for your favourite fruit

your favourite smells

girls you leaf through...

Having decided she should not have “indulged in the luxury of nostalgia” (the writing of the poem itself) she concludes: “I am reading the gray sky now/ in a sun-drenched translation.” The play between her poem (which she dismisses), its translation (into other tongues) and the “reading” of the sky as a “sun-drenched” translation creates a contradictory conclusion, as open as a flower or a question rather than old covers on a book or the lid of a coffin.

Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke takes to the high-wire of her subject, risking absurdity and death (as Lawrence Ferlinghetti would put it), and speaks across the borders, while turning death itself into a question, rather than an all conclusive finale.

There’s a curious U.A. Fanthorpe comment on the cover of Kate Foley’s collection “Laughter From The Hive:” “...(her) candid Dutch gaze at everyday objects, with the riddling English way of not explaining what it’s all about till the end...”

It is the “riddling English way” (another sieve reference) which draws the fault line between Anghelki-Rooke’s book and the other three volumes in my opinion. Mandy Coe, Sue Dymoke and Kate Foley share in common a splendid command of language, a keen observant eye and the means to extrapolate from the everyday, together with an ear for the “riddling” habit of storytelling in that anecdotal, whimsical English way.

Also shared by this trio of books is a lack of questions and literal question marks. With one or two fine exceptions, most of these poems are wrapped up in a conclusion - either as a punch line or as a riddle solver. It is as if a certainty has to parcel these well made poems in the manner of a short story or a story for children. Such resolution in some poems read or performed is fine, but is the lack of questions a particularly English trend now? A manner of writing as a new writing type?

Who’s sifting out the questions?

However, Sue Dymoke’s “Space Invader” in her collection “The New Girls” sparkles:

a loomingness of colour

a gloom-glow-push-pull

powder red presence

soft chocolate shimmer

midnight blue-black manoeuvre

brooding

forward

It is a response to a Rothko painting and here the poet doesn’t impose “the poem” over her response to this abstract visual. Instead, her response seems fluid, in the moment and visceral. Where Sue Dymoke lets this visceral, tactile electricity through the well crafted framework, her poetry is vibrant.

Mandy Coe’s collection “The Weight of Cows” is full of wonderful opening lines. Indeed, it opens:

We were nine years old when we killed Brendan.

Fantastic. However, for me the following lines kill off the poem as one knows, given its parameters, where the poem will take us:

An enemy sniper, shot

with a sawn-off broomstick...

It’s the broomstick. It’s a child’s make believe game. Death will be acted out but all’s going to be fine in the end.

What if the poem took another path:

We were nine years old when we killed Brendan.

An enemy sniper, shot with a sawn-off.

Now we don’t know where it’s going to go...

Kate Foley is an accomplished poet, obsessive in her observations and economic with her words. However, my favourite in “Laughter From The Hive” is her very long poem, “The Bleeding Key,” which tends to run in the opposite direction. Because of its large canvas, this poem carries elements of dramatic monologue and the poet expands her voice into the voices of her subjects:

Still dark, but dark as a lidded eye.

She sees the mummy case,

soft gleam of bitumen.

WaaaaAAAH!AlaaaAAA! A red cry,

furious, robust. IwannabreastbottlemiiiLK!

GIMME!

Brrum, brrrum, brUUM.

LemmeOUTlemmeOUT.

Heels on the empty shell.

The poem concludes tightly with: “dangerous dreaming/ our only key/ to home.” And it is here where there is “dangerous dreaming” her poetry becomes a risk rather than a recipe; where one cannot see a division between chaff and wheat, that she goes beyond “riddling English” in an exciting and engaging way.

January 31

"I MUST GET BACK TO MY ELEGY"

I stumbled across a couple of things this afternoon courtesy of The Page, which I’d look at more if I could remember to do so, or had the time. It just so happened I was at work today and had nothing whatever to do. When I say a couple, I mean three. One is some newish poems by John Ashbery (I guess they’re newish, anyway), one is a poem by Mark Halliday that I don’t remember seeing before, and the other is a short essay about Frank O’Hara’s “Personism”. Thank you, The Page.

I stumbled across a couple of things this afternoon courtesy of The Page, which I’d look at more if I could remember to do so, or had the time. It just so happened I was at work today and had nothing whatever to do. When I say a couple, I mean three. One is some newish poems by John Ashbery (I guess they’re newish, anyway), one is a poem by Mark Halliday that I don’t remember seeing before, and the other is a short essay about Frank O’Hara’s “Personism”. Thank you, The Page.